The pyramids. Stonehenge. Machu Picchu. The Acropolis. These man-made structures point to early civilisations, some of which are still shrouded in mystery. Yet these sites have become symbols of their modern-day countries.

The pyramids. Stonehenge. Machu Picchu. The Acropolis. These man-made structures point to early civilisations, some of which are still shrouded in mystery. Yet these sites have become symbols of their modern-day countries.

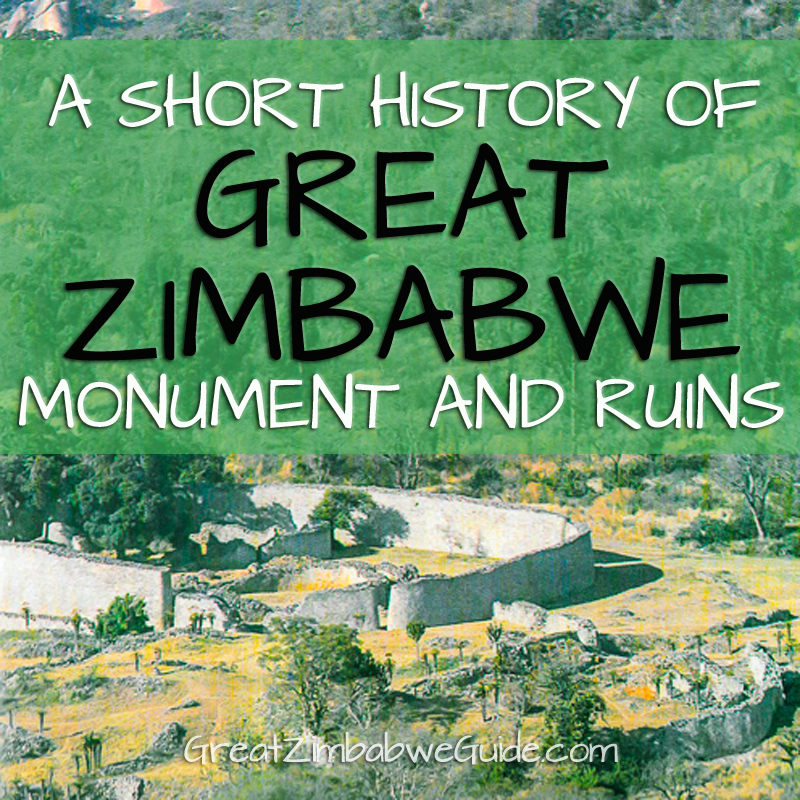

Zimbabwe has its own such monument in the south-east of the country, and it is called Great Zimbabwe (Dzimba-dza-mabwe, Houses of Stone).

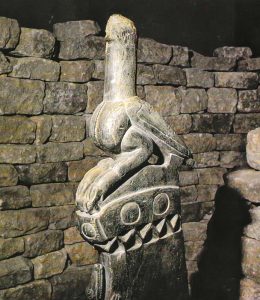

When Rhodesia became independent in 1980, the country took the name of the monument, and the nation itself was called Zimbabwe. One of the soapstone birds, found at the Great Zimbabwe site, has become the nation’s emblem, a central feature on the country’s flag.

One of the original soapstone birds. Source: Journey Through Zimbabwe, 1990.

The structures at Great Zimbabwe are the largest, and second-oldest, in sub-Saharan Africa. They have captured the imagination of locals and explorers alike. In 1531, Vicente Pegado, a Portuguese army captain from the trading port at Mozambique, described the area as follows:

“Among the gold mines of the inland plains between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers there is a fortress

built of stones of marvelous size, and there appears to be no mortar joining them…. This edifice is almost surrounded by hills, upon which are others resembling it in the fashioning of stone and the absence of mortar, and one of them is a tower more than 12 fathoms [22 m] high. The natives of the country call these edifices Symbaoe, which according to their language signifies court.”

Portuguese Explorers in the 16th Century believed that Great Zimbabwe was the home of the biblical Queen of Sheba, who visited King Solomon with gold and riches. Early theorists surmised that the structures could not have been built by Africans – it must have been the Egyptians or Phoenicians, who colonised the area in ancient times, they postulated. This debate continued for hundreds of years, and free research was hindered by British colonials and the Rhodesian government, who all told the world that it was inconceivable that local tribes could have been capable of the complex stonemasonry. Until the 1970s, evidence pointing to the local people was destroyed, and local schoolchildren were taught that the site had been founded by Phoenician colonizers.

However, archaeologist David Randall-Maclver claimed as early as 1905 that the dwellings were “unquestionably African in every detail”. He and other archaeologists were promptly banned by the colonial government. Over twenty years later, Gertrude Caton-Thompson came to a similar conclusion in 1929, but this was not accepted by the Rhodesian government. Both the British and Rhodesian power-holders had too much to lose if they admitted that local people had built such a formidable centre of trade. Raiders and amateur archaeologists had also removed and damaged important artefacts, which added an extra barrier to research.

However, in 1973, Zimbabwean- (Rhodesian-) born Peter Garlake published a paper before independence, in support of the evidence that the ruins had been built between the 12th and 15th Centuries by ancestors of the Shona people. This was an important milestone for Africans in reclaiming a history that had been propagandised for hundreds of years.

The site of Great Zimbabwe Ruins will continue to be a political tool however, as current-day politicians have continued to popularise new meanings and symbols for the monument according to current agendas.

Archaeologists have found glass beads and porcelain from China and Persia, as well as gold and Arab coins from the trading centre of Kilwa, testifying of the trade relations that the kingdom had with the outside world. The resources in the mineral-rich land nearby – gold, ivory, copper and bronze – are thought to be the currency of exchange. The capital was abandoned in 1450, apparently due to overpopulation and deforestation; the kingdom split and moved south to Khami.

Archaeologists have found glass beads and porcelain from China and Persia, as well as gold and Arab coins from the trading centre of Kilwa, testifying of the trade relations that the kingdom had with the outside world. The resources in the mineral-rich land nearby – gold, ivory, copper and bronze – are thought to be the currency of exchange. The capital was abandoned in 1450, apparently due to overpopulation and deforestation; the kingdom split and moved south to Khami.

Today, it is generally agreed that the builders of Great Zimbabwe were influenced by the Kingdom of Mapungubwe, and were Shona-speaking people of the Gokomere Culture incorporating what would become the Karanga clan and Rozvi culture. Construction started in around 1100 AD, and continued until 1450. In the 14th Century, it was the capital of an international trading state and home to over 10,000 inhabitants.

Great Zimbabwe was given UNESCO world heritage list status in 1986, due to the following criteria:

Criterion (i): A unique artistic achievement, this great city has struck the imagination of African and European travellers since the Middle Ages, as evidenced by the persistent legends which attribute to it a Biblical origin.

Criterion (iii): The ruins of Great Zimbabwe bear a unique testimony to the lost civilisation of the Shona between the 11th and 15th centuries.

Criterion (vi): The entire Zimbabwe nation has identified with this historically symbolic ensemble and has adopted as its emblem the steatite bird, which may have been a royal totem.

This website (GreatZimbabweGuide.com) is a wordplay on this monument of Great Zimbabwe. The website is a travel guide about Zimbabwe – all of it. Although “Great Zimbabwe” usually refers to this ancient city in the south-east, for us it’s a symbol of the country and its people as a whole: resilience and strength.

This website (GreatZimbabweGuide.com) is a wordplay on this monument of Great Zimbabwe. The website is a travel guide about Zimbabwe – all of it. Although “Great Zimbabwe” usually refers to this ancient city in the south-east, for us it’s a symbol of the country and its people as a whole: resilience and strength.

You can buy Peter Garlake’s renowned book on Great Zimbabwe on Amazon (affiliate)

Read more in the book Journey Through Zimbabwe (affiliate)More resources:

- See the post Great Zimbabwe travel guide for info on how to get to the ruins

- Here’s a route map and info on Walking around Great Zimbabwe Monument

- An excellent in-depth video from BBC’s Gus Caley-Hayford about Great Zimbabwe

- See this video from CNN about Great Zimbabwe

- Buy Peter Garlake’s book about Great Zimbabwe on Amazon

- Where to stay in Great Zimbabwe and Masvingo

- A fascinating workbook about the significance of Great Zimbabwe Ruins by The British Museum

- Visiting Great Zimbabwe Monument: Photo post

neyah

so final conclusion is that great zimbabwe was built but the native karanga shona speaking ?