Why write this article?

This website is not just about pretty photos of Zimbabwe’s game reserves; it’s about representing the current experience of travelling in the country and the context in which that travel occurs. If you haven’t read it already, please see the section on Currency and Money in Zimbabwe for specific tourist advice on the current economic context. I’ve visited Zimbabwe every year since I left it. During my August 2017 trip, I found that the country was, once again, a place of paradise and perplexion.

I wore several ‘hats’ during my stay: that of an ex-Zimbo returning home; a UK-based holidaymaker; and a writer wanting to document it all. I spent most of my time in the suburbs of the capital city of Harare, and I also visited Bulawayo (briefly) and Matusadona National Park (which you can read about here). If you’re planning to visit Zimbabwe’s National Parks as part of a packaged holiday, it is likely that you will be submerged in the utter paradise that is wild Zimbabwe, and you will see little of the Harare that I describe below. If you’re an independent traveller like me, or if you just want to read about the Zimbabwe that I saw, I hope this article sheds more light on this multifaceted country.

I wore several ‘hats’ during my stay: that of an ex-Zimbo returning home; a UK-based holidaymaker; and a writer wanting to document it all. I spent most of my time in the suburbs of the capital city of Harare, and I also visited Bulawayo (briefly) and Matusadona National Park (which you can read about here). If you’re planning to visit Zimbabwe’s National Parks as part of a packaged holiday, it is likely that you will be submerged in the utter paradise that is wild Zimbabwe, and you will see little of the Harare that I describe below. If you’re an independent traveller like me, or if you just want to read about the Zimbabwe that I saw, I hope this article sheds more light on this multifaceted country.

First impressions of Harare

One of the new additions to Harare Airport

One of the new additions to Harare Airport

I flew into Harare International Airport, ready to deal with the much-discussed “cash crisis”, armed with fresh US Dollar notes, paid my visa fee with the exact notes required, and stepped into the dimly-lit arrival hall. I was greeted by taxidermied African animals in large display cases. The displays are clearly well-intentioned, meant for showing off the thrilling creatures that live in Zimbabwe’s National Parks. I tried to take comfort in the idea that someone “high up” was making some sort of effort, or an investment even, to appease tourists. Yet these Victroian-esque exhibits look morbid and ironically Colonial, especially away from their usual museum setting. Perhaps this is symbolic of the lack of understanding that officials have of today’s ethically-minded and eco-conscious Western travellers, who are more likely to see these exhibits as creepy than inspiring. Or perhaps the taxidermies are aimed at a completely different demographic, such as the trophy hunting industry. Maybe I’m just over-interpreting a few dead animals that have probably been collecting dust since the 1950s.

Signage in Harare: unavoidable

Signage in Harare: unavoidable

Until recently, the main road from the airport into the city had been a construction site. It took several painstaking years to create a double carriageway, apparently hopeful of an influx of visitors. The construction is now finally complete, and the dug-up earth has been replaced with an army of gaudy advertisement signs. To say that these signs are large is an understatement: they tower above the horizon, appearing so close together that they seem like some sort of shock-factor psychological experiment. The signs advertise cars, brand-name perfumes, Zanu-PF slogans, and events for local celebrities such as self-proclaimed prophet Emmanual Makandiwa, whose miraculous talents include filling event attendees’ bank accounts with money.  Now, although these banners are ugly in the extreme, they give the impression that some companies in Zimbabwe are making enough money to pay for such things. On a less hopeful note, I had to ask: have councillors and businesses become so desperate, and have they lost so much national pride that they’re willing to disfigure their city in this way? Perhaps local councils have so many other battles to face that they don’t have time to be concerned with signage regulations.

Now, although these banners are ugly in the extreme, they give the impression that some companies in Zimbabwe are making enough money to pay for such things. On a less hopeful note, I had to ask: have councillors and businesses become so desperate, and have they lost so much national pride that they’re willing to disfigure their city in this way? Perhaps local councils have so many other battles to face that they don’t have time to be concerned with signage regulations.

One of Harare’s many garden cafes

One of Harare’s many garden cafes

There are still pockets of beauty in the capital, where businesses have given priority to their natural surroundings. I delighted in visiting the many outdoor eateries, where I could sit in the beautiful gardens with a cappuccino and carrot cake, watching my son play on the grass. During my time in Zimbabwe, these cafes were often humming with people, a very happy sight. There are few equivalents of these outdoor utopias in UK cities, mainly due to the weather and space disparity, and I treasure Zimbabwe’s social spots almost as much as its National Parks. Of course, these venues are for those who can afford a frivolous cup of coffee, something we often take for granted, and something that the majority of Zimbabweans simply cannot do.

“Village Walk”, a recent extension to the already-large shopping centre in Borrowdale

“Village Walk”, a recent extension to the already-large shopping centre in Borrowdale

I was surprised to see expansion and hints of investment around the capital. The shopping centres in Arundel and Borrowdale have nearly tripled in size in the last ten years, despite the country’s turmoil. Walking into suburban supermarkets to see well-stocked aisles (albeit with predominantly imported goods), clean floors and freshly-painted walls seem a far cry from the news reports of Zimbabwe’s eclipsed economy, or cash crisis.

A new supermarket in Borrowdale, Harare, August 2017

A new supermarket in Borrowdale, Harare, August 2017

Going to Borrowdale Village on a Saturday morning, I was met with the sight of well-dressed families (of all races) drinking milkshakes and eating waffles in smart-looking restaurants; there were cinemas screening the latest releases of international films at very reasonable prices; and fountains effusing mist into the balmy air. If you were airlifted into this spot, I doubt you would be able to guess that you were in one of the poorest countries in the world.

Decadent treats at a central Harare coffee shop

Decadent treats at a central Harare coffee shop

Harare’s young professionals, entrepreneurs and academics go to pop-up wine bars and sushi restaurants; they listen to local musicians under gold-tinted fairy lights, clinking their glasses under the stars. In other countries, they would represent the middle class. Yet there is no middle class here, there are the rich, the poor, and the government. Rich and poor alike are subject to police roadblocks dotted throughout the city, being fined for any reason the police choose.

Hararians dine under the stars at The Horsebox Bar

Hararians dine under the stars at The Horsebox Bar

Rich and poor alike stand in queues at the bank to withdraw the stipulated maximum limit of US $50 (sometimes less). They are charged $12 for 250 grams of butter at the supermarket. The rich are lucky enough to afford elderflower-infused gin on a Friday night, but they live in a country where they cannot pay for that gin using their own cash.

Local musicians Chris Wright and Tinashe Makura perform at The Horsebox Bar

Local musicians Chris Wright and Tinashe Makura perform at The Horsebox Bar

Going cashless for the wrong reasons

On the occasion that I used a fifty-dollar US note to pay for a meal, I was met with a sharp intake of breath and a wide-eyed look from the teller, as if I’d pulled a handful of diamonds from my pocket. US Dollars, which up until recently were Zimbabwe’s main legal tender, are now extremely scarce. Bond notes are following in their wake.

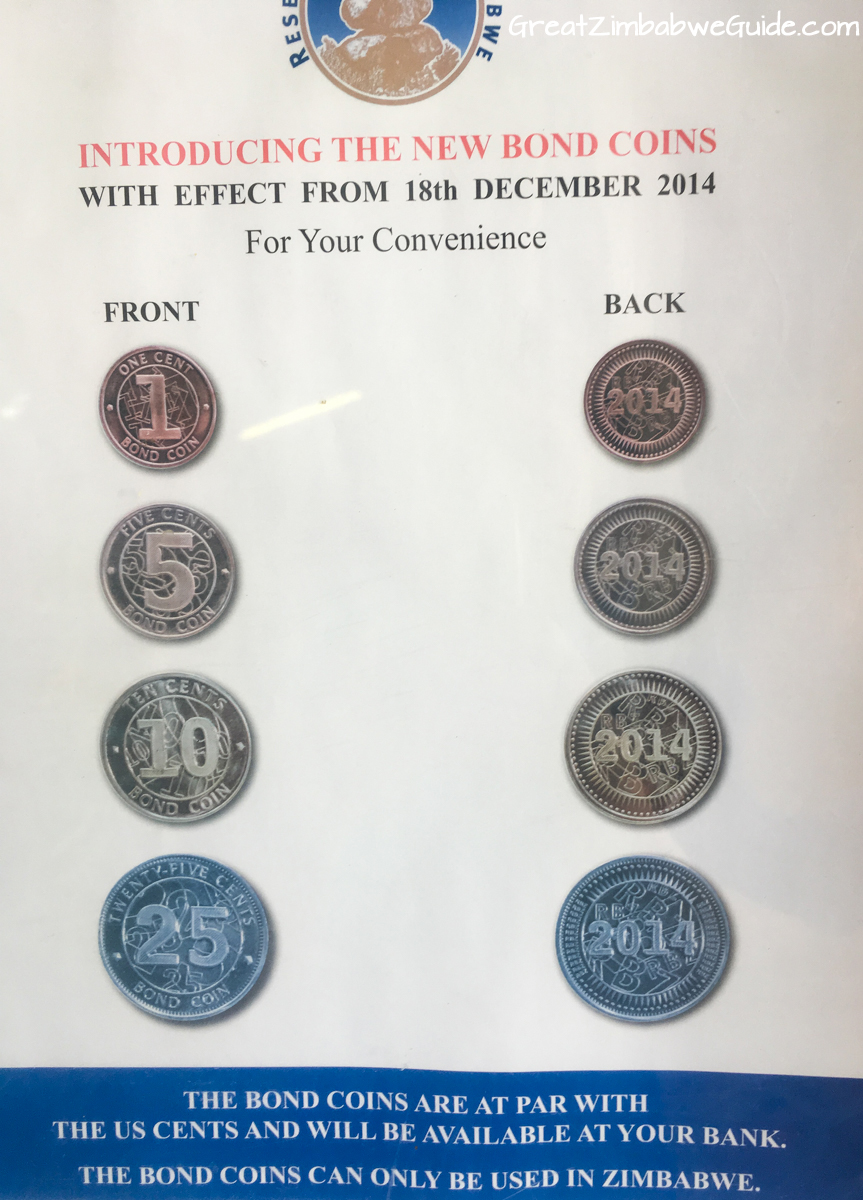

Bond notes are not officially a currency; they are legal tender

Bond notes are not officially a currency; they are legal tender

People have started using mobile transactions and swipe cards, but these come with a price: some businesses charge a 20% surcharge for cashless transactions. Only a small percentage of Zimbabwe’s population has bank accounts; partly due to the bank charges, partly due to the lack of banks in the rural areas, and mainly due to a lack of trust after the hyperinflation of the early 2000s. In a land where informal trade is widespread, cash is king.

In early 2008 (above), the price of one toffee apple was 1000 Zimbabwe Dollars, and that was after a few zeros had been removed by the government

In early 2008 (above), the price of one toffee apple was 1000 Zimbabwe Dollars, and that was after a few zeros had been removed by the government

You may think: What’s the problem? Aren’t most societies moving away from cash? In the case of Zimbabwe, it is a symptom of a much bigger problem. The country imports more than it exports, which means more money is leaving the country than coming in. The mining, manufacturing and farming industries aren’t producing enough goods to export or to feed the local population. Zimbabwe’s trade deficit was $3 billion in 2015 alone; that represents the money that has left the country in just one year.

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe secured a $250 million-dollar ‘export incentive scheme’ from Egypt-based Afreximbank, using this to create Bond Notes and coins − and now even those are running out. Yet another $600m line of credit from Afreximbank has just been announced (September 2017). Most citizens cannot open non-Zimbabwean bank accounts: all of their money is either in local banks or hard cash. If the government were to repeatedly use money from the banks to pay the army and civil servants, or if the Bond Notes devalued to the point of hyperinflation, the population of Zimbabwe would become paupers once more. (Article continues below the photo.)

Bond coins were introduced in 2014, to be “at par with the US” Dollar

The effects of the cash crisis

What effect does this have on the tourist experience? Right now, in 2017, short-stay visitors aren’t heavily inconvenienced by the cash shortage because they can bring cash with them into the country. They would, however, run into problems if they wanted to withdraw money within Zimbabwe, or make international bank transfers to certain local businesses. I had a fantastic time in the cities and in Matusadona National Park. I can say without hesitation that my 2017 trip was definitely much better than any visits taken between 2005 and 2009. It is much easier to plan a holiday using US Dollars than difficult-to-buy Zimbabwe Dollars. I didn’t experience any power cuts or fuel shortages during my 2017 visit, and there was plenty of food in supermarkets and restaurants.

A popular fresh-produce supermarket in Harare, August 2017

However, it is clear that locals are feeling crushed by the cash shortage, and that the situation is approaching a head. Landlords, shopping outlets and informal transport providers are charging 20−25% extra to customers who cannot pay in cash. The burden is being felt by businesses and by everyday people in both cities and rural areas.

Many Zimbabweans I spoke to said that everyday life is almost as bad as it was ten years ago, because they are struggling to to pay for their everyday provisions, and they fear that there will be shortages of basic commodities in the next few months. It is distressing to imagine that Zimbabwe could be heading into that territory again. See some of my photos from that time, showing poorly-stocked shop shelves and fuel queues.

This photo of a near-empty supermarket was taken in 2008, when the inflation rate was estimated at 250,000,000%

This photo of a near-empty supermarket was taken in 2008, when the inflation rate was estimated at 250,000,000%

The cash crisis is just a symptom of the dire political situation. In 2008, opposition party MDC claimed victory in the parliamentary elections, heralding hope, and Morgan Tsvangirai formed a Unity Government with Robert Mugabe. US Dollars were then adopted instead of the Zimbabwe Dollar, and for a time, Zimbabwe looked like it was on the road to recovery (it was then that I started this website). However, targeted violence and power-stealing tactics against political opponents slowly chipped away at MDC’s foothold and Zanu-PF resumed its grip on power in the 2013 elections. Since then, party infighting and power struggles have taken precedent against any meaningful development, leading to the current state of affairs.

Artisans sell their work on Harare’s streets, reliant on cash sales and tourists; both of which are in short supply

Artisans sell their work on Harare’s streets, reliant on cash sales and tourists; both of which are in short supply

There may well be facades of wealth in suburban Harare, but this is not a complete picture of the country. Talking to locals, there is a sense of trepidation and resignation in their words; almost as if they’re intimately familiar with the storm that is coming their way, but unsure of how to protect themselves or of what damage will be done.

What is my advice to travellers?

The cash crisis doesn’t have to prevent tourists from enjoying Zimbabwe’s wildernesses for short-stay trips

The cash crisis doesn’t have to prevent tourists from enjoying Zimbabwe’s wildernesses for short-stay trips

Zimbabwe is still extremely rewarding for short-stay visitors, with fantastic opportunities for intimate and uncrowded wildlife experiences. It is a safe and welcoming country, especially for people travelling with tour operators and private lodges. As long as you pay for the majority of your trip in advance, the lack of cash shouldn’t affect you much. The political/economic situation is indeed serious, but at the moment it is mainly affecting the regular people of Zimbabwe, not visitors. Dedicated advice can be found here.

Foreigners can help by keeping up-to-date with those in Zimbabwe who are speaking up for the good of the people, such as ThisFlag Movement, Fadzayi Mahere, David Coltart, and Magamba TV. Those ‘Likes and Shares’ on Facebook really do help to spread the word and keep this on the international agenda. You can also help Zimbabwe just by visiting: tourists help keep locals in jobs and indirectly helps to fund conservation projects.

You might also like

- See other articles on this site talking about Zimbabwe’s wider context

- Is it ethical to visit Zimbabwe? I think so. Read more here

- Life in Zimbabwe, 2008: Snapshots from the archive

- Here is a comprehensive and up-to-date timeline of Zimbabwe’s history

- Read my Harare city travel guide

- Read my Victoria Falls travel guide

- The biggest travel blogging conference is coming to Zimbabwe in 2018: are they making a deal with the devil?

- Read the book ‘When Money Destroys Nations: How Hyperinflation Ruined Zimbabwe, How Ordinary People Survived, and Warnings for Nations that Print Money‘ by Haslam and Lamberti

- Trace the movements of the Zimbabwe Dollar on Wikipedia

C. Harrup

Insightful article Beth. Thanks for taking us back through time and elaborating on a few current issues. However, I think that as of this past month of September 2017, things have taken a bit more of a turn for the worse, having seen the fuel shortage videos, long queues and cash crisis further escalating for everyone up there.

I will look forward to your next blog article to keep abreast of the current situation up there and hope that there will be a few more comments on this article in the near future 🙂

All the best.

Great Zimbabwe Guide

Thanks for your comment! Yes indeed, the picture of Zimbabwe in September 2017 has moved on from August 2017 already. Hopefully readers will connect to some of the social media accounts mentioned at the end of this article to stay up-to-date with how the situation is changing.

All the best! – Beth